Q: Where were all these lines made fast?

A: There are some traditional patterns and schemes, but there are no fixed rules!

And as far as research can tell, there never had been any fixed rules - another ship, another mate, another scheme.

Also, when fine weather sails are "swapped" with heavy weather sails, more lines and blocks are added. So the bitts and fiferails provided

space for a varying range of lines! Or, in some cases, several lines of the same type (e.g. buntlines) maybe belayed to one pin.

In fact, multiple belayings to one pin happen more often than one might think, as long as it is "OK" for the sailors who know.

On the other hand, it is very easy to add a new bitt as needed. Modern sailing ships keep to the rule of one pin per line, though.

The scheme and the rigging system is very logic, when You get to know it more deeply...

Q: Are there any plans or schemes?

A: There are. But there are several "types":

Modern Training Ship Schemes

Belayings on the "Sagres II", seen in Bremerhaven 2005.

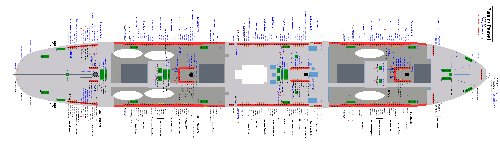

And the complete belaying scheme of the Sagres II is this ...

... in original Portoguese. I got the scheme copies when I visited the ship and got contact to the cadets.

I drew this scheme image and kept the original terms.

For translations into English and other languages, go to the Maritime Dictionary (menu above).

Schemes like these are available for trainees who sail on modern training ships

Modern Reconstructions of Ancient Schemes

Only a few authors have contributed to this:

- Anderson (1955): Seventeenth Century Rigging

- Anderson (1927/88): The Rigging of Ships in the days of the spritsail topmast, 1600-1720

- Longridge (1961): The Anatomy of Nelson´s Ships

- Marquardt (1992): Eighteenth-century Rigs & Rigging

- Underhill (1965): Masting and Rigging - The Clipper Ship and Ocean Carrier

And, of course, most of the books in Conway´s series of "The Anatomy of the Ship" :)

NOTE: All these reconstructions are subject to discussions, as different authors come to completely different results.

Compare the plans for the

USS Constitution (1797)

Ancient Schemes ("Originals")

These are utterly rare and remain almost unpublished - they are "rotten and forgotten" in the archives, reachable for truely insisting researchers only.

I know only one single book im my library of 1000 volumes

that at least refers to these plans: Edson´s "Ship Modeller´s Shop Notes", 1979. He citates a proposal by

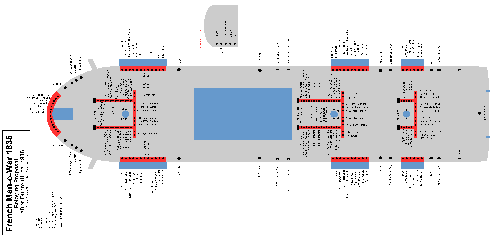

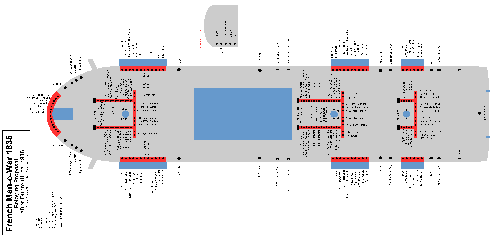

Dubreuil (1835) for a French Man-o-War

(Shop Notes pp.197-200):

Edson gives also a lot of comments on this plan, some details that he believes not have been different - his speculations so to speak.

Edson refers to a variety of other sources:

- Coste (1837): no title given :(

- Dubreuil (1835): the plan citated, but its provenance is not mentioned.

- Charles G. Davis (1846) description of the Sea Witch (no title given :( )

- Lescallier (1791): Traite du gréement

- Romme and Lescallier: works of 1780, but no titles given :(

- Missiessy (1798): no title given :(

- Steel(1794): Steel´s Elements (I have this book - it contains no schemes, just some hints)

- "Dutch books of about 1840" that confirm Dubreuil´s scheme for merchant ships.

Wow - where can I find these ???

The question can also be approached by the three "types" of sailing ships:

- Modern Sailing Ships (and some replicas) which are still seagoing - they are few, some 50 ships only all over the world,

when we talk about Tall Ships.

These are the only ships having a full functioning rigging.

- Museum Sailing Ships in a dock or in a harbour, having a quite reduced, static rigging.

- Model Sailing Ships in museums or private collections, which reconstruct the rigging to some extend and quality.

I. Modern Sailing Ships

The German Navy training ship Gorch Fock II, 2006

|

Today, almost any tall sailing ship is a training ship for cadets of the worlds navies. Some of these did serve as merchant ships in their early life

but now they only serve as school ships, like the "Sedov". Most of them were designed as training ships, like the "Eagle" of the "Gorch Fock" class or the "Mir" class.

A few of them are luxorious sailing cruisers for the very rich. The most famous maybe the "Sea Cloud"s.

And some are rare replicas of famous ancient ships rebuilt anew, to serve as training ship as well as maritime research,

about how these old ships were sailed.

Examples are

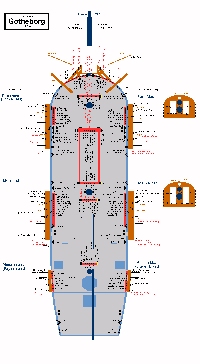

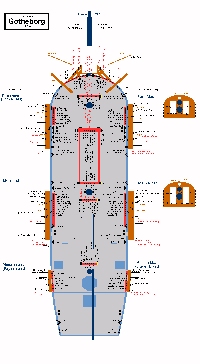

the Swedish "Götheborg III" (an East India Man), and the "Endeavour" and "Bounty" replicas.

These are the only ships having a full functioning rigging.

Since seamenship, the knowledge of how to sail a tall ship, is quite unknown to the average modern people, they have to be instructed how to handle the rigging.

And everything has to be explained.

These instructions are only available as small-issue manuals in the navies. But often they are simple copies of belaying schemes - which maybe altered, too.

The average cadet crew does not bother if any changes were made, they just need an actual scheme of where to find which line, on a simple piece of paper.

Then they memorize it during their daily duties. Most of the cadets only stay a short time ever on that sailing ship, and only the few bosuns and rigging masters

know more about the quite specific rigging of their ship. So it is fair to say that only some hundred persons in the whole world may have that knowledge.

Each of the modern sailing ships has its very own belaying scheme, adapted to its own rigging layout,

which is also adapted under re-riggings or rebuildings.

In a class of ships, like "Gorch Fock" or "Mir", where

several ships share a similar rigging, the belaying scheme is also similar - but not the very same! Small differences can be observed, and these ships are sailed

in different manners. And as these ships are repaired and re-rigged many times (about once every year), schemes are altered here, too. In other words: there is no "original"

condition of any ship, it is changed and developed all the time. The cadet instructions may give You just the actual scheme used.

|

II. Museum Sailing Ships

Stationary museum ship Passat in Lübeck, Germany

|

These ships are tied in a dock or in a harbour, having a quite reduced, static rigging, if any. They still look "impressive" and "nice",

but when You look closer You find the most belaying pins unused - because the running rigging is almost completely removed, as it is not needed

in the harbour, the ship will never go to sea anymore and the costs to keep a full but unused rigging in shape cannot be justified ...

So You can see the entire standing rigging (stays, shrounds and backstays), but the running rigging is reduced to yard halyards and braces; and those

are often simplified (fixed), because nothing is supposed to run any longer in that ship. So of course, no sails are bent to the yards,

so all reefs, bunt and leech lines are omitted.

We can be very happy that these ships are preserved at all.

But they are of limited use as an example for running rigging reconstructions.

And, as they are restored with chronically limited funds, some new rails for instance are completely without any belaying pins ...

|

III. Model Sailing Ships

Altonaer Museum, Hamburg, Germany

|

Scale mopel ships in museums or private collections. They show a reconstruction of the rigging to some extend and quality.

Ancient and Modern Ship Modelling - A Change of Focus

- The hobby modeller of today wants a model to "look nice", it is just for fun.

There is nothing wrong with this :) Many are over-demanded

when it comes to the rigging, and that is what their models look like - sorry :)

- The ancient Prisoner-of-War modeller:

they never needed any plans, they were emprisoned seamen, rebuilding *their own* ship as a model.

This explains the quality of the

famous POW-shipmodels made of bones! Why did they make models of bones? Well, they had nothing else to do in their prisons,

they had no other work to achieve some benefits, and: they had no better material available than bones.

- The shipyard modeller: a professional, with a long craftsman tradition. His working place is still there

when a shipyard builds a new ship - ships are recently modelled virtually with computers!

The only difference of our modern times is, that the model is made after a bunch of

detailed technical plans, whereas in ancient times, when plans were rare or non-existent, the model itself

was the example for the real ship to be built! In fact, entire classes of rated ships were built using the

Admiralty Models! The Victory is only the most famous one of her class.

- The historic modeller: only very few can truely be called historic ship modellers, who are also maritime researchers - which I am not.

They reconstruct old ships as models using any source available.

They preserve an old maritime heritage that would be lost otherwise.

They go into the archives and spend 99% of their time for research, before they start building, making every part by themselves!

When You start becoming a historic modeller, the frustration is big - nobody can answer Your humble questions.

It is hard and time consuming to get the right books and plans.

It is even harder to read them and to check them for "mistakes".

The shipyard modellers and the historic modellers make the finest models. These are utterly rare ...

And then almost noone would ever see any "mistake"...

"So why wasting time for this?!"...true, it contains some kind of masochism, as one modeller said :)

|

These fine museum ship models can be used as fine examples.

But: they, too, are just another reconstruction,

and in case of museums these models are restored, altered, rebuilt, even if carefully, so the example quality is limited, even

on the finest exemplars like the "HMS Prince" in the British Museum - built in the 17th century,

the rigging has been added in the 19th century. No remark about this at the showcase ...

We can be lucky that we find these models preserved at all,

but they still often hide as much as they show.

Due to a modelling tradition, many models do not show sails and its gears, only masts with square-braced yards.

If they show sails, it is hard to trace the leading of the lines. Quite often, making photos in the museums is prohibited!

And if we can trace lines, sometimes we still find strange things ... which is no problem for the model,

as it is finally nothing more but an eye-catcher to attract visitors

at the display case. And then, the model that was built in thousands of work hours, is looked at just for some seconds for a short "wow".

Only enthusiasts like me could spend whole days in a museum...

What sources do we have?

I. Original Plans and Depictions

Sail Plans and deck plans can be found in

many books, but 90% are reconstructions (e.g. by McGregor) and "only" show the the outline of the sails, without their halyards, sheets and the other lines,

or deck layout and positions of the rails respectively. These plans are also preserved in the archives - the first exact plans were drawn by Af Chapman in Sweden

("Architectura Navalis Mercatoria").

A belaying plan explains all pin´s and clamp´s lines, which results in a very dense plan of information.

And each belaying plan is individual for every sailing ship, since the ships were individual. But before 1920, when the sailing era was already over,

belaying plans are not preserved, if they ever existed.

Belaying plans were "introduced" in the era of Training Ships, to teach the ropes to the cadets

as fast as possible, because they were onboard only a limited time...

For instance, I am lucky to have a copy of a belaying plan of the 4-mast-barque Pamir. I got it on my visit of her surviving sister ship,

the Passat, in Lübeck, Northern Germany, today a stationary museum ship.

And I only got this plan because I happened to meet an old sailorman (who had been sailing with her in the 1950s) giving a guidance tour to another visitor group (I was coming alone).

When he finished the guidance tour, I could talk to him, and he gave me the plan - the till girl selling tickets did not even know what such a plan was (of course she didn´t),

nor that those were in stock for sell ... so I would not have had that chance without meeting that nice old seaman!

And this is my more modern version of the Pamir plan, in English and German:

In some rare cases, some depictions and early photos can give some hints. But of course they show only that a pin was occupied by a line - but not which line...

The fore rail on starboard of the East India Man replica Götheborg III, June 2009

|

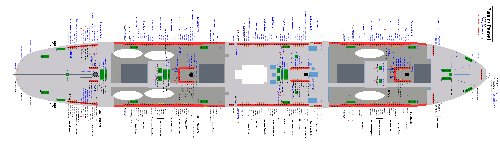

Here is the scheme of the "Götheborg III", as of June 2010.

The belayings here in Swedish and English

|

All plans we have today about old ships are entirely reconstructions by maritime researchers in the past 100 years.

NOTE: for studding sails, which were used exceptionally only (between 1700 and 1900), there were no dedicated pins! Those lines were belayed to any suitable part of the rigging.

I have gone through literally 1000 books for this in the past 20 years.

Here is a list of books that contain some rigging and belaying plans - they are few:

| TITLE | AUTHOR | PUBLISHER | YEAR | PAGES |

| American Sailing Ships - Their Plans and History | Davis, Charles G. | Dover Publications, NY | 1929/84 | 196 |

Bemastung und Takelung von Schiffen des 18.Jahrhunderts

(with 4 scheme reconstructions) | Marquardt, Karl-Heinz | DK | 1986 | 480 |

Eighteenth-century Rigs & Rigging

translation of [Bemastung und Takelung von Schiffen des 18. Jahrhunderts]

(with 4 scheme reconstructions) | Marquardt, Karl-Heinz | Conway | 1992 | 330 |

Captain Cook´s Endeavour

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | Marquardt, Karl-Heinz | Conway | 1995 | 136 |

Cutty Sark

The only reference to my knowledge for her belayings) | Hackney, Noel C.L. | PSL | 1974 | 96 |

Die deutschen Segelschulschiffe

(contains the plan of the Gorch Fock) | Koop, Gerhard | Bernard & Graefe Verlag | 1989 | 148 |

| HMS Beagle - Survey Ship extraordinary | Marquardt, Karl-Heinz | Conway | 1997 | 128 |

Le Vaisseau de 74 canons - Tome 3

(showing a French Ship of The Line) | Boudriot, Jean | Éditions des 4 Segnieurs | 1975 | 280 |

Les Grand Voiliers

(contains many different belaying plans) | Bathe, B.W. | Edita | 1975 | 260 |

Masting and Rigging - The Clipper Ship and Ocean Carrier

(showing a general scheme) | Underhill, Harold A. | Brown, Son & Ferguson | 1965 | 290 |

Mayflower

(with a reconstructed belaying scheme) | Hackney, Noel C.L. | PSL / DK(German Translation) | 1970 | 80 |

Modellbau von Schiffen des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts

(German; there is also a Dutch translation of it) | Hoeckel, Rolf | DK | 1966 | 128 |

Modeller af vore gamle sejlskibe - vejledning for modelbyggere

(Denish) | Kisling, H.M. | Borgens Forlag | 1972 | 168 |

| Plank-on-Frame Models and Scale Masting and Rigging Vol I+II | Underhill, Harold A. | Brown, Son & Ferguson | 1958/1974 | 160+160 |

Rigging Period Ship Models

(excellent, but based on a museum model) | Petersson, Lennarth | Catham Publishing, London | 2000 | 120 |

Rundhölzer, Tauwerk und Segel

(sowing a Ship of The Line of the 19th century) | Schrage, Klaus | Koehler | 1989 | 188 |

Seventeenth Century Rigging

(3 reconstructed schemes) | Anderson, R.C. | Marshall | 1955 | 146 |

Ship Modeller´s Shop Notes

(contains many different belaying plans, inluding the USS Constitution!) | Edson, Merritt | Nautical Research Guild | 1979 | 216 |

Ship Models - How to Build Them

The clipper Sea Witch! | Davis, Charles G. | Dover | 1925/1986 | 140 |

Skeppsboken - Livet ombord på en ostindiefarare

THE book about the Götheborg III replica | Ahlander, B. + Langert, J. | SOIC | 2009 | 144 |

The 24-gun Frigate Pandora

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | McKay, J. + Coleman, R. | Conway | 1992 | 128 |

The 32-gun Frigate Essex

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | Takakjian, Portia | Conway | 1990 | 128 |

The 44-gun Frigate USS Constitution

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | Marquardt, Karl-Heinz | Conway | 2005 | 128 |

The 100-gun ship Victory

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | McKay, John | Conway | 2004 | 120 |

The Anatomy of Nelson´s Ships

(excellent, with the belayings if the HMS Victory) | Longridge, Nepean | Percival Marshall | 1961 | 280 |

The Armed Transport Bounty

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | McKay, John | Conway | 1989 | 120 |

The Four-Masted Barque Lawhill

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | Edwards + Anderson + Cookson | Conway | 1996 | 128 |

The Frigate Constitution and other Historic Ships

(the first reconstruction of the USS Constitution in the 1920s) | Magoun, F.Alexander | Bonanza Books | 1928/(1980) | 154 |

The Masting and Rigging of English Ships of War 1625-1860

(3 reconstructed schemes, referring to Anderson) | Lees, James | Conway | 1979 | 196 |

The Rigging of Ships in the days of the spritsail topmast, 1600-1720

(3 reconstructed schemes) | Anderson, R.C. | Dover | 1927/1994 | 278 |

The Schooner Bertha L Jones

(The Anatomy of the Ship series) | Greenhill, B. + Manning, S. | Conway | 1995 | 128 |

Yes, that´s it! Just 30 books out of 1000, only 3%.

It is remarkable that most of these books are quite old and out of stock long ago...and the newer ones are all reprints.

There are some books that are assumed to contains such a plan, but they do not; e.g. Longridges´ extremely detailed book about the Cutty Sark

provides no belaying plan (instead, he just mentions that he provided his model of the Cutty Sark with "some more pins" than suggested in the plans - he does not say how many - , and shows this on photos).

In his other great book about the HMS Victory, he does provide these details to the reader.

The major part of this book selection was issued by Conway as "The Anatomy of the Ship" series (some of their books do not show a belaying plan, though).

Most of these books contain "only" reconstructed schemes, especially when we even do not know how the ship looked like at all, as in the case of the Mayflower or the Columbus ships.

What formed our common clichée about those ships are - again - reconstructions based on almost unavailable data from the documents. On the other hand, it is remarkable

what can be reconstructed, using those utterly rare information ...

NOTE: Not even one of these books / plans shows belayings schemes for studding sails - which indicates (but not prooves!) that there never were

dedicated pins for these sails.

There are plenty of books about ship modelling, containing masses of detail information about

rigging, BUT belayings; they all "stop" when they explained how the rails and bitts looked like ... makes me wonder. Hundreds of ropes are coming down to deck,

and they tell about thousands of details important for the enthusiast modeller. They explain the purpose of any of these lines, even how they were used, the commandos etc, BUT

they all keep "silent" when it comes to belayings. Very strange, in my humble opinion ...

We can find some recommendations in some OLD lecture books for seamanship,

but even most of those do not give a belaying plan; they describe any detail - but this; obviously it was considered common sense that had no need to be mentioned.

"It reeves through ... and belay." Period. Where to belay ... "on deck", "on the rail". Where on the rail was that? Pity, the ancient bosuns knew ...

How to reconstruct a belaying scheme?

Without the patterns (see below), the only vague rules can be derived by applying physical mechanics. There was only one vital rule:

no line coming down to deck must interfere

with another line, simply in order to keep the rigging functioning well. For the belayings,

there is only a certain "sphere of probability", because after all,

it could be anywhere on an appropriate bitt or rail.

Beyond those physical considerations, we only have some known belaying patterns, some still used today, how to group lines on a bitt or a rail.

It is interesting to compare some plans of similar ships, because then You see how different belaying schemes can be - even on the very same ship!

For instance, I know two different schemes for the Swedish schooner Gladan, showing that the scheme had been altered after a decade; but You will only notice

that when You compare both manuals...

In reality, belayings are mixed up in the hurry, and corrected when cleaning the decks after a sail manoeuvre.

Although there are some common patterns, it can be quite misleading to take the plans for ship A

trying to apply it to ship B ...

So, after all, You never know, You are on Your own, the reconstruction becomes YOUR personal re-invention - it is a problem

that You share with any other historic researcher.

It only depends on how deeply You are into rigging ...

A Set of Questions and a Set of Patterns

In the last five years, I have reconstructed many belaying plans on paper.

After all, any reconstruction is a guess. There are no proofs whatsoever that the belayings are "correct".

They are only "probable", and any "errors" can only be reduced to this probability. Well, that´s what science is all about :)

Here are the questions that arise:

How did the line come down to deck? Thus You have a more or less defined "area of probability"

where the line had its belaying position.

|

Begin with the "origin" of the line (e.g. the yard arm or the sail´ clew) and then reconstruct its "path" down.

Most of these pathes can be seen on contemporary depictions, they show these details

quite well. We have many pictures from the side perspective, but - naturally - none from the top perspective.

All details "behind" the rails are hidden from the viewer.

Most lines lead first to the mast top, and then down to deck. Some other lines may come down directly from where they origin, like the braces.

A line that "reeves" through the top still can have many pathes to a rail, as long as no other line is interfered:

- to the fiferail (or a "spider band") at the mast foot

- to the rail - directly

- to the rail - but through a fairlead

- to a shroud clamp (fairleads may be applied here too)

Those lines can belay anywhere in this "sphere".

All combinations are possible. But, some patterns were applied for ease of use.

Forget about the exact number of pins on the bitts and rails. One of the easiest parts a ship carpenter made and repaired often was

taking a wooden beam, shaping it to a rail or a bitt, and drilling holes for as many belaying pins as needed.

What counts are the lines coming down on them, the rigging define their numbers.

And that is how many pins were needed.

But of course, some pins were belayed doubled with different lines, occasionally.

It takes much training and practice to handle all the sail gears right.

One of the probable reasons for accidents at sea was: chaos of belayings and an untrained crew,

provocating the capsizing of the ship in normal winds!

|

How heavy was the burdon of those lines?

Light lines are all ropes for sail furling: the clewlines, buntlines, leechlines, bowlines

and downhauls (or inhauls). Their leadings are in pairs and symmetric

for port and starboard; sometimes You find "single" middle buntlines.

(All landlubbers who do not understand go here)

50% of the running rigging consists of light lines. The belayings of those are very often altered.

Most of them come down directly from the mast top, so they can be belayed anywhere around the mast, that is: the rails, the fiferail and/or spider band,

or even on shroud clamps.

Braces are lines to swing the yard around, to let sails catch the wind most effectively to drive the ship.

The lower braces are

heavier and thicker than the upper braces, because the lower sails are larger and have more strain.

All brace leadings are in pairs and symmetric for port and starboard.

With some changes through history, lower braces lead down almost horizontally, most often to the pinrails, the upper braces first lead to a mast or

a stay and then down on deck, that is: to a pinrail or a fiferail; as said, anywhere on them.

Heavy lines are for sail setting, withstanding the ultimate strains: the halyard and the sheets,

taking the burdon of the yard, the sail, and wind pressure.

On windjammers, they were partially made of iron/steel chains instead of ropes!

These lines are strengthened using heavy double or triple block tackles.

Square sail sheets go most often directly down to the bitts or fiferails

around the mast (exeptions did of course exist).

Halyards (derived from "haul-yards") for hoisting

can be symmetric, but in many cases they are single and belay to one side only.

Square sail halyards are the heaviest lines in the running rigging, they bear several tons of weight,

of the yard, the sail and sometimes of up to 20 sailors in the footropes of the yard.

Sheets of square and stay sails are in pairs and symmetric for port and starboard.

There are sometimes single sheets for small staysails, though.

In most cases, the spanker also has double sheets (and tacks on lateen spanker yards). All lower sails

(the "courses") have very heavy sheets leading aft to the rails and tacks leading forward to the rails.

Lower sails have heavier lines than upper sails, because upper sails were only set

in fine and calm weather - to gain as much wind force as possible, but they were furled as soon as

a gale came up, for they would just blow away then. The courses and topsails had the strongest lines of all.

There was a pattern to order belayings by the order of the yards (from lower to upper).

The less heavy topgallant and royal sail gears were at the end of the rails or on shroud clamps.

How did the seamen work with the ropes? This is teamwork. A single man can do almost nothing.

There were "watches", groups of seamen having different duties,

scheduled in shifts of 4 hours work and 8 hours free, in a 12 hour rythm.

The ship was manned 24 hours a day, so a ship with a crew of 60 had always 20 men working, at least.

A man on "free watch" also had much to do...

Most sail maneouvres need many hands, inlcuding the bosuns! Hauling the topsail yard on the Götheborg, June 2009):

Ancient seamen knew what to do by heart for their daily work.

When the captain just said "Make sails!", the bosun gave a number of more specific orders like

"Ease topsail buntlines!", "Man topsail halyard, all hands!", and seamen knew what to do.

They learned their profession at sea like any other craftsman, starting as a ship boy, during many years.

When a new ship was manned, there were "sea trials", to train the people and form them into a new crew.

That training was essential, an untrained crew would loose the best ship...it is reported that the largest ship of her time,

the spanish four-decker "Santissima Trinidad" at the Trafalgar battle, was defeated

not by the superior British gunners, but primarily because of poor crew training of the Spanyards.

And the American frigate "USS Constitution" alone

defeated *two* British Ships of the Line more than once, because the Old Ironsides

had a well trained and motivated crew - and good gunners...

Where were the bitts and rails for belayings? How did they look like?

Bitts and pinrails are the basis for belayings. They were one of the easiest wooden pieces a ship carpenter

could make: a beam with holes to take the pins. They were repaired and reshaped very often, and changed

many times during the lifetime of the ship.

The ships were different. More sails, more lines. Other sails, other lines.

And other mates, other belayings...

Patterns for Bitts and Pinrails

The bitts and rails were not fixed, they were altered and reshaped many times.

This is why there were so rarely documented on the deck plans.

- The Fife Rail

- The Pin Rails

A starboard pin rail of the of the Sedov, as seen in Hamburg, 2004

|

Pin rails are long beams with many belaying pins (up to 40!), placed under the shrouds and the backstays. All rails are symmetric

for port and starboard.

|

- The Shroud Clamp

|

On the inner side of the shrouds, clamps were often attached to take light lines

(all upper sail gears were considered light lines, including their sheets!).

Shroud clamps were always there when no pin rail was installed, as on the forecastle

of the old Royal Navy ships. The disadvantage is obvious: the seamen had to

go out to the shrouds, which was very dangerous in a battle...later Ships of the Line had higher bulwarks for that reason.

|

- Knights and Kevels

|

The old ships until 1800 had also these kind of belaying points.

The knight was a vertical beam on deck, around the mast, with a sheave hole at the bottom and a "head" at the top,

to belay one or two heavy lines (mostly halyards). These knights were the supports for the bitts,

and were integrated into them.

The kevel was a cross of two beams to belay very strong ropes under the pinrails,

mostly the lower sheets and tacks. Kevels were replaced by big metal clamps or bollards on windjammers

for the same purpose.

|

- The Pins

|

Today, each line has its own pin. This was not always the case in ancient times.

The first pins of course were wooden, the last Tall ships had pins of steel of very heavy lines,

while those for lighter lines, like the buntlines, were still made of wood. The old sailor that I met on the Passat

told me that they had steel and wooden pins in use.

The more back into history, they were rare or no pins, the line was belayed on the beam, the rails

or the shrouds

without pins. It just takes a knot ...

|

Belaying the Ropes: Patterns through the Eras

It is just one of these small details on deck ... the way how buntlines are attached to lower sails is very well known.

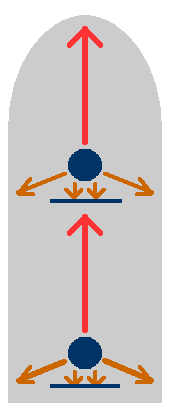

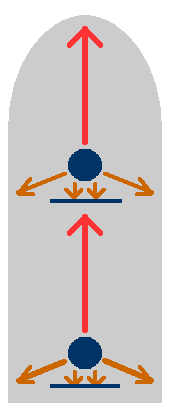

All physically possible leads and belaying areas, seen from above

|

The challenging detail for any modeller is: when these ropes finally go down from the last block on or over the yard, how do they lead then.

And there are patterns for different eras and centuries.

To my knowledge, there are no original belaying plans originating from before 1900. But there were some patterns, that follow physical principles:

the ropes lead down to the most nearest place on deck, either to the mast foot bitts, or the rails on the side of the ship. Or, they may also lead

forward, following the stays of the standing rigging.

|

|

Belayings on Old Ships - The "British Pattern"

There is an old, very important source of information: Steels´ "Elements of Mastmaking and Rigging" from 1794 (with many reprints).

It is THE source of old ships with the highest historic "authority". It could be assumed that shipbuilders in Great Britain kept close to the rules

and patterns presented in these books.

There is a detail very different from "modern" sailing ships, namely with the clippers and windjammers: according to Steel,

the lower buntlines (of the courses) lead foreward along the mast stay!

Steel gives no information about exact pin positions to belay, so it can be only guessed that those line belayed on clamps on the stay, or

on some knights or pins nearby around the mast foot of the forgoing mast.

This pattern has been used also on the first North American sailing ships and frigates in the British colonies, for obvious reasons.

One belaying scheme reconstruction of the

USS Constitution (1797) (published only in "Modellers Shop Notes", plan by Edson/Vogel/Spicer)

follows the same "British way". But that plan is a reconstruction by Spicer based on notes of Vogel, who in his turn based on reports

of Edson. Nobody knows who of these, and how far, added his own considerations to alter the plan. After all, it is a traditional, historic pattern.

I can recall how much I was amazed to see such a "strange" lead forward when I saw it for the first time. It was in Steels book, I have a reprint.

I remember I could not believe it (I am continental, so to speak). "It cannot be!" I thought. "This does not work. The lines will move when the yard is braced,

that makes no sense ..."

Well ... I know that from a continental point of view, the British do have a number of "strange" traditions :)

But not all British modellers follow Steel. When the master modeller C Napean Longridge built his giant model of the

HMS Victory, in the 1960s, he let the lower buntlines go to the same mast where they came from, and published this in his book

"The Anatomy of Nelson´ Ships" ... did he have a reason to decide "against" Steel, and apply a "Continental Pattern"?

Would the lead of the main buntlines go directly forward along the main stay, it would be a problem: when the yard is braced into the wind,

the buntlines of one side would be tight, and the other side very loose and could thus even damage the sail in the wind,

so some sailors would be needed to adapt their belaying during the bracing - and this would be "unnecessary work" ...

An adaption to the porblem would be, to have a number of blocks above the center of the yard, unter the top platform,

and let the lines lead down from there. Then the yard bracing would cause no more problems ...

The buntlines of the upper sails (the old topsails and topgallants ["t´gans"])

of the old ships were not many, contemporary depictions show regularly only 2 topsail buntlines

and sometimes 2 topsail leechlines. The topgallant sails had only one buntline in the middle, or none at all. Old royal sails were even "flying",

with nothing more than their halyard and the sheets; they were set in calm weather only.

The lead down of those "upper lines" was never described,

but it can be assumed that they were made fast around the same mast biss or rails; it is physically arbitrary, where exactly that was.

Well, it is of course our modern rationalism that rules out anything "unnecessary". It could have been real in those times that this

"unnecessary" work had in fact been done by some sailors who were onboard so many. These men were given even the dullest jobs,

just to avoid boredom of doing-nothing, and thus to prevent giving people time to think about their poor situation; in order to prevent mutiny.

It could also be that sailors themselves kept to

these traditions for the sake of tradition as a sailors pride. Thus, developement of the rigging was very slow in these times.

I cannot give a pattern picture here. There were too many different deck layouts, and too many variants and adaptions of the pinrails and bitts,

with the size and the purpose of the ship (warship or merchant ship, large and small).

Belayings on Old Ships - The "Continental Pattern"

The "continental" rigging (of France and all other non-British navies) was, as far as we know, different here:

those buntlines went down to the bitts and rails of the same mast that they come

from. When no rails were in place at the sides of the ship, they installed shroud clamps instead.

Again, I cannot give a pattern picture here. There were too many different deck layouts, and too many variants and adaptions of the pinrails and bitts,

with the size and the purpose of the ship (warship or merchant ship, large and small).

Belayings on "Modern" Sailing Ships - Clipper and Windjammer Patterns

Modern sailing ships - British and Continental =) - belay all their buntlines at the rails along the mast shrouds, or sometimes,

the lower buntlines on a pin "somewhere" around the same mast; because these "XXXL"-lower sails can have up to 10 bunt- and leechlines.

The modern sailing ships applied more "logic" schemes, and repeated them on almost all masts of the same rigging.

Lines of the same type, which were moved together in the same direction (braces, clewlines and buntlines)

were often grouped together for that very reason, in order no to mix them up with other lines serving a completely different part in the rigging.

In the 19th century, a typical square sail mast had the following arrangement:

A special detail is the arrangement of the yards halyards, forming a kind of semi-symmetry.

The next-upper halyard was belayed to the "other" side-rail, so we find an alternation

of the pins, "jumping" between port and starboard.

The order of alternation tradionally started with the (lower) topsail on the port rail (that is: to the left side) for the Fore mast.

The Main mast was a mirror of it, starting at starboard (to the right). And so forth, when the ship had more

square rigged masts...

but: other countries, other traditions. Some ships had the same scheme "unmirrored" applied on all masts.

In reality, the sailors were instructed by the bosun knowing all the lines by heart. In those days, people and sailors (who often could not read)

used no plans, but memorized

everything they needed to know. That is why the knowledge had been almost lost for us today.

Questions? Feel free:

j_gelbrich@gmx.net

|